Affective Altruism

2024-02-29I've been a close follower of the Effective Altruism (EA) movement for almost a decade now. It's been equally gratifying and surreal to see EA grow so much in its influence. In a time of tremendous darkness, and an endless string of silver bullets promising salvation from it, there's something comforting about the presence of a group that cares so seriously about measurable improvement.

EA's rise has also been frustrating though. For years and to no avail I've been trying to convince Effective Altruists of a glaring weakness to their movement, which has only grown more glaring over time. Now, it feels like this issue is quietly at a breaking point. I'm taking it upon myself to make one last attempt to speak to it as loudly and clearly as I can, even if it might come across a little harsh. EA is not good at communications.

As I write this, Open Philanthropy (OP) — a prominent figurehead of the EA movement — is hiring for a Communications Director. It feels safe to say that the context for filling this position is both a product of the organizations's natural growth trajectory, but also a reaction to external circumstances from the recent past that have abruptly highlighted the value of communications.

This post is framed as a direct response to OP's Communications Director job listing. What I've written is a strategic blueprint for how I would carry out the role, which to be clear, I have actually submitted an application to and would love to be hired for.

Realistically though, I think my chances of landing this job are slim. As such, the main reasoning for writing this post is because contained within its proposed strategy is a generalizable case study for how communications can be improved not just within OP, but across EA.

With that out of the way, let me explain what I mean when I say EA is not good at communications.

The talent that surrounds OP is impressive. It's not an easy thing to build a team that is extremely competent without profit as a core motivator. Still, I believe that many EA-styled organizations, of which I include OP, suffer from an achilles heel. As tends to be the case for concentrated groups of very smart yet culturally-alike people, Effective Altruists discount the importance of speaking legibly to out-groups, as well as the general value of external perceptions. This ultimately is harmful because, counterintuitive to its focus on the niche and neglected, EA's impact imperative is fundamentally concerned with how mainstream tracts of society views it.

Whether lead poisoning, nuclear extinction, or AI alignment, the common thread shared by nearly all EA cause areas is the desire for increased attention. EA itself is fundamentally built upon the premise of neglect. The point of identifying and cultivating a new cause area is not for it to remain a fringe issue that only a small group of insiders care about. The point is that it is paid attention to where it previously wasn't. Mainstream advocacy work is much more than a cherry-on-top; it's essential for solving the structural shortcomings of society's narrow and misdirected attention, which to be clear, is more narrow and misdirected than ever.

And yet, when I look at the day to day communications practices of EA orgs like OP, I don't see a sufficient respect paid to this basic trait of modern advocacy work. In the job listing for the Communications Director role is an illuminating description that speaks to the heart of what I want to push back against:

While we want to make a positive case for our work, we care much more about maintaining accuracy and rigor than telling a compelling narrative, or otherwise making ourselves “look good.”

I understand this line is more of a casual value preference than any deeply entrenched communications philosophy. Still, I can't help highlighting it for epitomizing a two-sided fallacy that is endemic to the landscape of EA-adjacent communications work.

For one, there seems to be a working assumption that "looking good," and creating "compelling narratives" are in contradiction with "accuracy and rigor." To the contrary, I strongly believe these things are not mutually exclusive. If you think they are, you're probably not a skilled communicator.

Secondly, there seems to be a sunk cost fallacy around committing to the bit of rigor. Even if looking good was locked in a zero-sum relationship with rigor, unflinching adherence to the later comes at a cost that is not sufficiently internalized by Effective Altruists (EAs). Steely, bayesian logic is simply incompatible with how wider swaths of the population communicate. Whether or not this is unfortunate is entirely different from whether or not it's true. Not seriously entertaining the benefit of communicating legibly in exchange for the hypothetical cost of sacrificing rigor ultimately hurts EA's goals.

I want this post to leave readers better understanding why messaging and image are so vital, and why the current state of affairs does not suffice. Using the case study of OP, I want to illustrate a way forward, a way to improve the strategy and execution of philanthropic communications work without sacrificing the core of what makes EA unique.

If all goes well, the post will make several things clear by its end:

- What EA and OP's communications practices currently look like and how they fall short

- Why communication reforms are valuable to pursue

- What the contemporary communications environment looks like

- What reforms to OP's communications practices might look like

What is 'Communications'?

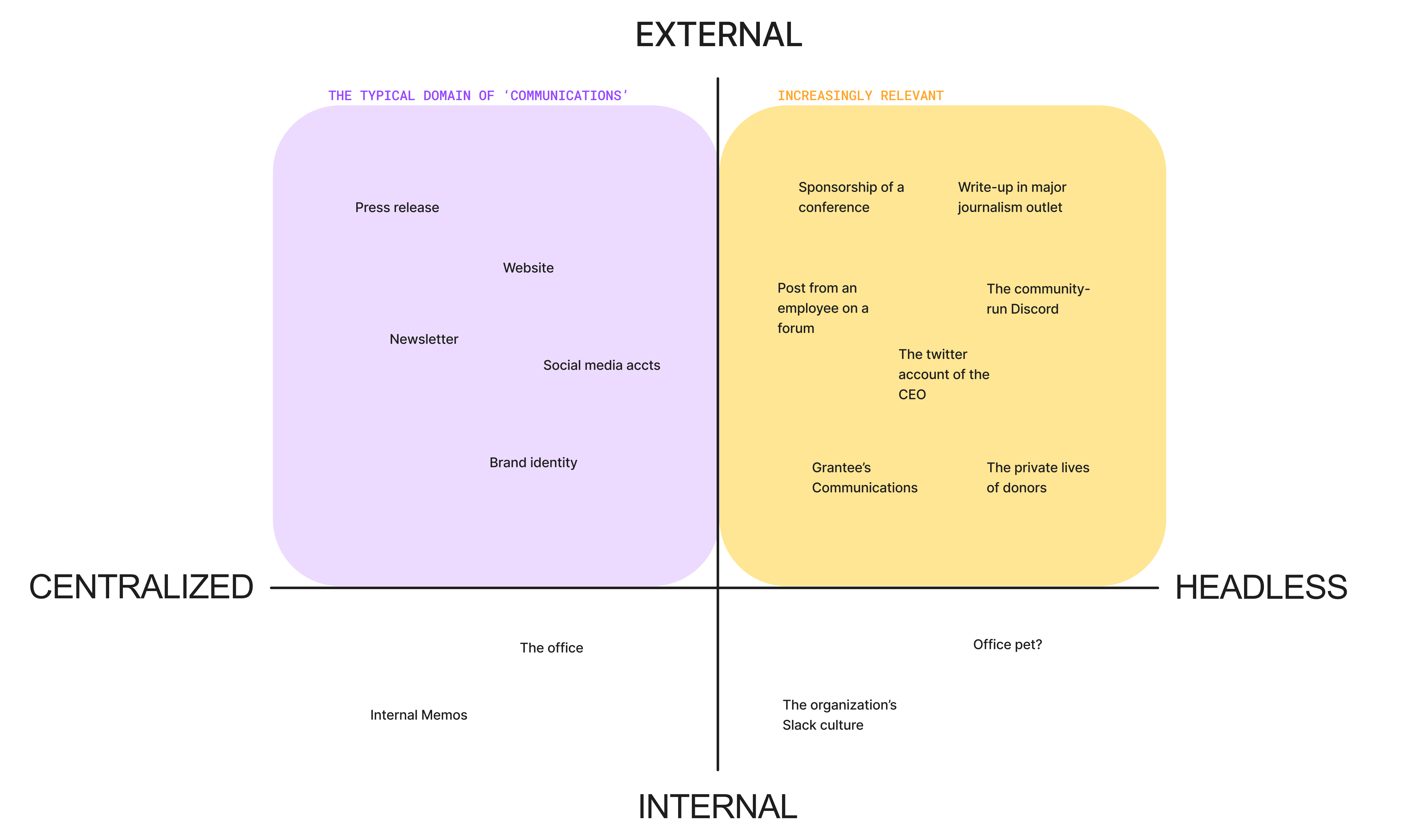

First, we need to quickly define what 'communications' means in the context at hand. I define communications most broadly as any exchange of information or ideas, through any medium, and from any source, that ultimately reflects back on an entity, be it a singular 501c3 or something more abstract such as movement like EA. I know this sounds like it includes a lot but that's sort of the point. Modern communications is fairly medium agnostic, always-evolving, and not necessarily top-down. Since we care more about the outcome than the means though which it was technically generated, it's best to take a wholistic approach in understand what communication is and what it isn't.

We can add at least one level of specificity and think of communications here as 'nonprofit communications,' which has the ultimate goal of advancing a discrete mission. Tactically speaking it covers:

- Branding — including everything from a visual brand to headless branding

- Public Relations — the intentional act of understanding and guiding public perception

- Grantee Communications — how an organization speaks to grantees at all points along the grant making lifecycle

- Web Design — how an organization presents itself on its website, sometimes called 'information architecture'

- Content Marketing — publishing a blog, newsletter, report, magazine, etc. (some overlap with web design and social media)

- Social Media Management — an organization's presence on social media platforms

- Physical Interfacing — how an organization presents itself IRL, be it at its office or a conference

- Advertising — the creation and placement of promotional media, paid or otherwise.

- Internal Communications — also sometimes referred to as knowledge management, how internal stakeholders speak to each other be it note taking or chat apps.

- Donor Relations — crafting messaging specifically for donors at all points along the fundraising funnel

For the context of OP specifically, some of these categories are more important than others. I've ordered the bullet points above in loose order of tactical priority (which will be explained more later in this post).

Another way to think of the landscape of communications is to consider a 2x2 with headless/centralized on one axis and internal/external on the other. We typically think of communications as pertaining to the upper left quadrant (external+centralized) in the photo above. Increasingly though, communications deals with its headless manifestations too. Internal communications are important (lower half of chart) but less so in the context of OP and this post.

How communications works in Effective Altruism

To understand what can be improved about the state of communications in OP we need to form a view of how things currently work.

What I've written above might make it seem like the communications practices in EA and OP are nonexistent but they are actually quite robust. It's just that they're robust only within a very narrow style and medium which can be summarized as text-heavy and long-form.

EA is fairly conscious about the importance of reaching out to the general public, although I would argue it isn't the most adept at sticking the landing. Consider for example one of the central communications nodes of EA — 80k Hours. Despite being more concerned with outwardly evangelizing the ideas of EA than any other entity, I don't think of 80k Hours is particularly well-suited to attract individuals who aren't already predisposed to EA's ideology. 80k's communications style can be described as neutral and scientific. This goes along with its preferred mediums, which are books, long-form text posts, and several hour-long podcasts. The subject matter is predictably nerdy and makes little attempt at translation despite a consistent appeal to clarity. These preferences reveal a pattern that is repeated across EA. In seemingly prescribing to the belief that diminishing intellectual rigor is more important than attempting accessibility, EA-styled communications are exclusionary to the very people that would benefit most from them.

Consider another main avenue for internal communications in EA — the EA Forum. For something that’s been designed so intentionally over the years, the EA Forum is starkly impenetrable to any style of communication that’s not lengthy text posts. On the forum you’ll find almost no graphics or color, which reflects not just the design opinions of a forum's creator, but the communications culture of an entire community. It's this culture of impenetrability, and the implicit bias it represents against any alternative form of communication that I think is worth questioning.

To be charitable, there seems to be at least a minority of individuals in EA who care about communications (shout out to the twitter accounts EAheadlines and Frances Lorenz). 80k Hours for instance, recently launched a side feed podcast they call '80k After Hours,' which in their words "[includes] things like how to solve pressing problems while also living a happy and fulfilling life, as well as releases that are just fun, entertaining, or experimental." And while many of the episodes do seem to live up to this description, it's hard not to raise an eyebrow when you see titles like "forecasting the war in Ukraine" or "mental health challenges that come with trying to have a big impact."

When someone tries to call out the need for better communications, but does so in a way that perpetuates the original problem, that's when you know that there might be more structural issues at hand.

Recently I came across an incredibly rare thing — an EA meme that actually made me laugh. Perhaps this was because it was a meme that was making fun of the way Effective Altruists make memes. To conclude, I thought it would be a succinct way to capture what I'm trying to say about how EA communicates.

How communications works in Open Philanthropy

EA is not the same as OP, and while the two share a lot of traits, notably amongst their communication habits, it's important to understand that OP is an autonomous entity with its own objectives and resources.

OP is not historically as interested itself in directly evangelizing the EA movement compared to organizations like 80k Hours (which it funds). It's a grant-maker that doesn't solicit grants requests, nor really even has a fundraising practice. OP could hypothetically operate in mystery and silence similar to McKenzie Scott's Yield Giving, which is known for surprising a wide range of grantees with large amounts of money virtually out of the blue. But as its name suggests, this is not how OP operates. The organization was founded on the basis of appealing to transparency into the philanthropic process because this was believed to serve a purpose. If more effective charities and philanthropies were methodical in documenting their hypotheses around impact, then the learnings from this could give other organizations a foot up when trying to be effective themselves.

This value of transparency would become an intrinsic part of how OP communicates. As opposed to needing to attract donors or grantees, the main pillar of OP's communications practice can be thought of as education and even more specifically, cross-philanthropic capacity building. Illustrating this is the extensive amount of effort that OP puts into its grants database, explaining its cause area selection, a blog, 'notable lessons' page, and the website that houses all of these things together. If I was a researcher at philanthropy or charity that was attempting to be more impactful, theres no doubt I would find a lot of value in the extraordinary measures OP takes to, even if just through text, clearly write about its process and thinking.

As you might guess though, I have a bone to pick.

Similar to the general shortcomings discussed earlier with EA, OP's communications are dense and dull. Browsing OP's website, visitors are left in an uncanny valley between the labyrinthian text blocks of a wiki and the hollowness of a mid 2010s SaaS startup. One of the only places on the website outside of the hero that unique images can be found is three clicks away from the home page on individual grantee profiles. Team member headshots aren't displayed on the team page but one click deeper. Bespoke icons that are used to identify cause areas like Farm Animal Welfare are set up to be a refreshing visual anchor, yet are designed with a subdued color palate and flat vectorized aesthetic that ultimately leaves them blurred into one another. In this design logic we see a seemingly intentional decision to obfuscate and disembody the humanity that's both behind and the focus of OP's philanthropic work.

It would be interesting to spend more time researching the ethnographic origins of the EA's aversion to more human-centric styles of communication. Of course a big part of the explanation likely lies in the rationalist and utilitarian strains of thinking that are only a few degrees removed from EA's founding ideology (that, by the way, historically emerged from literally talking to computers). Still, there's something that's always not quite added up about the extent that EAs devalue anything that could be described as storytelling. How could a group that is so driven by effectiveness, not see the abounding evidence that all humans, even the smart ones that live in the Bay Area and don't believe in god, are inherently drawn to communications that play nto their prosocial and visual instincts?

I can begin to empathize with the reasons why this pattern of communications found its way to OP specifically. Perhaps, as exemplified by the line from the Comms Director job listing quoted earlier, telling a "compelling narrative" was intentionally never part of assignment, as it was feared to detract from the "rigor" of OP's work. Perhaps it was feared that an ornate design prone to breaking and aging would be a poor use of precious resources. Perhaps the broader point about EAs is relevant to OP as well — that its organizational and communications culture is such that logos and pathos are seen as mutually exclusive. Maybe speaking empathetically or narratively was simply seen as inappropriate to the main communication goals of OP, which to reiterate, is not soliciting donations a la Save The Children but actually speaking in a capacity building context to other philanthropic practitioners. Much like a medical journal isn't tasked with embodying the warm and fuzzy, neither is OP.

All these things might be true and still I don't think they would justify not pursuing a more legible style of communication. Now we're finally at a point where I can begin to argue why.

Discourse: Erratic, Attention: Deficit (DEAD)

There are two main reasons why I think OP should rethink its style and mediums of communication. The first point is hopefully not deserving of anymore than a few lines of explanation on account of how ubiquitous it is. Attention spans are at an all-time low. This doesn't just apply to teens on TikTok. It applies to adults, professionals, and even the academic types who were supposed to be the last vestige of all things slow, long, and boring. Coming to terms with this reality does not necessitate that scientific journals need to start posting fancams or face filters. There is still, and hopefully will always be a vital place in the media ecosystem for the type of writing that OP does. The attention deficiency crisis is best thought about as something that needs to be reckoned with, but not slumped down to. For an organization like OP, this means it should continue to publish the clear, long form writing that it does best, but also create more accessible on and off-ramps that are attention friendly.

The second reason why OP should rethink its style and mediums of communication is less obvious, but I think equally important. In today's media and discourse environment, notions of objectivity, nuance, or credible neutrality are not the strong foundations that they might have once been. The battle between rationality and irrationality goes on as it always will, but at the moment the pendulum is seemingly far swung in later's direction.

While it receives its fair share of healthy (and occasionally unhealthy) criticism, to my knowledge OP has never faced an existential PR crisis. It's not inconceivable to imagine how one could transpire though. Despite straightforward intentions of doing the most good, OP distributes capital to philanthropic causes that typically operate outside the Overton window. It does so with a certain tolerance for ambiguity and risk. When operating from this position, no amount of good intentions can protect against the inevitability of the unforeseeable. Nor do good intentions mitigate the reality that philanthropy itself is increasingly viewed with ire by the public.

Consider OP's involvement in AI safety and the relationship it has had to mainstream news around OpenAI and, to a lesser extent, the Horizon Institute. I hesitate to even bring up these examples because they're likely redundant for OP staff at this point, but for the unfamiliar I'll summarize the broad strokes. OP distributes capital to a number of organizations and individuals that attempt to decrease the risk of undesirable outcomes from advanced AI. Some of these grants (or investments) are successful at bringing attention to the issue, but do so in a way that, to some skeptics, walks the line between preventing dangerous AI and inadvertently advancing it.

From here we can project all the irrational, yet very real directions this scenario could go in. Here's the most heavy-handed one. An unexpected forward lurch in capabilities goes public and the well-intentioned philanthropy is caught in the middle of a complex ideological rift between divergent camps that argue for AI moratoriums on the one hand and acceleration on the other. Looking for a scapegoat, the public latches onto a preexisting narrative that suggests that philanthropic actors are shadowy boogeymen wielded by the elite to pull the levers of society. Politicians savvily mirror the frustrations of their constituents and play into their conspiracies. An OP program director, who has very little to actually do with this larger public debate, is suddenly subpoenaed to testify in a congressional hearing where they are forced to answer an ill-tempered congress member's questions. It might go something like this:

"Is your organization funded mainly by the fortunes of one of the founders of Facebook?" "Yes, that is correct." "Do you think that AI poses a small risk of killing my children in the future?" "Yes ... I suppose that is possible." "And did your organization help fund the leading AI firm, OpenAI?" "Yes, that is true."

This vignette portrays the worst-case scenario of an unfortunate and unlikely PR blunder. At the same time, it illustrates a conceivable point about what can happen to honest, good-faith, credibly neutral actors in a discourse environment that emboldens the sensationalist and divisive. In the game of big, world-changing ideas, every person and entity, whether they are deserving of it or not, can find themselves suddenly in the center of the crucible.

As we saw in the fallout of FTX, or the rapid accelerationist-driven backlash to the EA movement following Sam Altman's surprise ousting from OpenAI, it does not take much for members of the public to latch onto a perceived enemy. As Dustin Moskovitz pointed out in a recent post — not all EAs are the same. But as much as EAs love to argue how their movement contains multitudes, it's aspirational to think that non-EAs reserve the same multitudinous view. In a media landscape built upon starter packs and Types-of-Guys, you live and die by the label, regardless of whether you think it's accurate. The alt-right probably contains multitudes too. That doesn't mean its monolithic title isn't a useful or convenient label to reach for.

For OP this means that to some extent the actions of all EAs reflect back on it. Alongside the earlier point about attention spans, this is something that should be dealt with head-on and proactively. By the time that a PR agency is employed to help put out a fire, it is already in some ways too late.

I don't want to be mistaken for implying that OP isn't aware of the discourse or attention environments it sits within. I think that the campaign to hire a new communications director is if anything evidence of an appreciation for the necessity of a solid communications strategy. Nonetheless, I want to emphasize that the challenge at hand isn't best fought by taking cues exclusively from the corporate PR playbook of ten years ago. Less than ever can be gained from merely trying to take the high road. Even the most well-meaning and neutral of organizations like OP have to face the music.

The exciting thing is that if these hurdles are crossed, what lies ahead for OP is not just a more resilient brand but a wholesale improvement in the way outsiders perceive it. An additional benefit is that OP stands to positively shift the public’s image of EA too. That whole living and dying by the label thing? Turns out it works both ways. OP might be vulnerable via association to the demerits of other EAs, but it also can use this association to lift up the reputation of the entire movement.

What good communications work looks like

Armed with a better understanding of the modern communications environment, we can finally begin to talk about the important stuff — not the challenges or imperatives of communications work, but what good communications work actually looks like.

Some of these changes I'm advocating for aren't complex, nor should they seen as overly disruptive. They literally are superficial in nature. Here's one suggestion tailored for the OP website: use more visuals. Virtually every page on the OP website should have at least one graphic or piece of multimedia. Not necessarily an image, but some kind of visual anchor. Every blog post, every grant entry, every sub menu. Ideally these graphics should have a loosely-aligned visual style. Graphics should not be seen as filler material but an alternative vehicle for expressing the same ideas that OP's writing does.

Speaking of writing, another easy-to-implement strategy with outsized returns would be to publish writing that could be described as storytelling. I'm not talking about sensationalizing or narrativizing the tone of grant profiles or research reports. These things are the bedrock OP's work and should remain the same. In addition to this information-heavy writing there should be guideposts, ideally written from the perspective of an identifiable person, that help orient newcomers to the complexities of OP's decade-plus of evidence gathering. Think of a blog post that talks about the OP's 'Notable Lessons' with respect to same human fallacies and irrationalities that gave way to these lessons in the first place. Or perhaps Alexander Berger should use his twitter platform to speak directly towards the experience of running OP. When I say that humans are attracted to stories, the basis for this is not a lust for gossip but a desire for orientation. In appealing to the canonical narrative ark, we allow for a version of world-building that neutral, voiceless writing is not capable of.

While it might seem difficult to execute, the style of visual and textual communication that I'm describing — one in which data, narrative, and image are simultaneously wielded in a way that does not comprise their rigor — is by no means unprecedented. We could of course point to the work of many different journalism outfits that adeptly balance visual evidence and storytelling. In the realm of EA specifically, Future Perfect is a bright spot for its highly evidential and engaging writing. But since OP is not in the business of journalism, here are some other examples that might be more relevant. CarbonPlan's research is unashamedly data-driven, well-designed, and multi-modal. The NY Times' R&D lab also publishes research posts which do a great job of documenting internal processes by adding video of the actual employees behind the work. Neither of these research posts skimp on textual substance. In doing so, they model how engaging visual anchors can be used to invite distracted readers to spend more time with deeper ideas in the form of text.

A final compelling example of writing can be seen in the auxiliary publications of the Jain Family and Berggruen Institutes, which are respectively Phenomenal World and Noēma. Phenomenal World and Noēma are both interesting case studies in how a philanthropic actor can experiment with more engaging, discursive ideas without directly attributing them to its core brand or relating them to its day-to-day work.

A brighter surface layer invites audiences to engage with more complex ideas beneath

The dark arts of branding

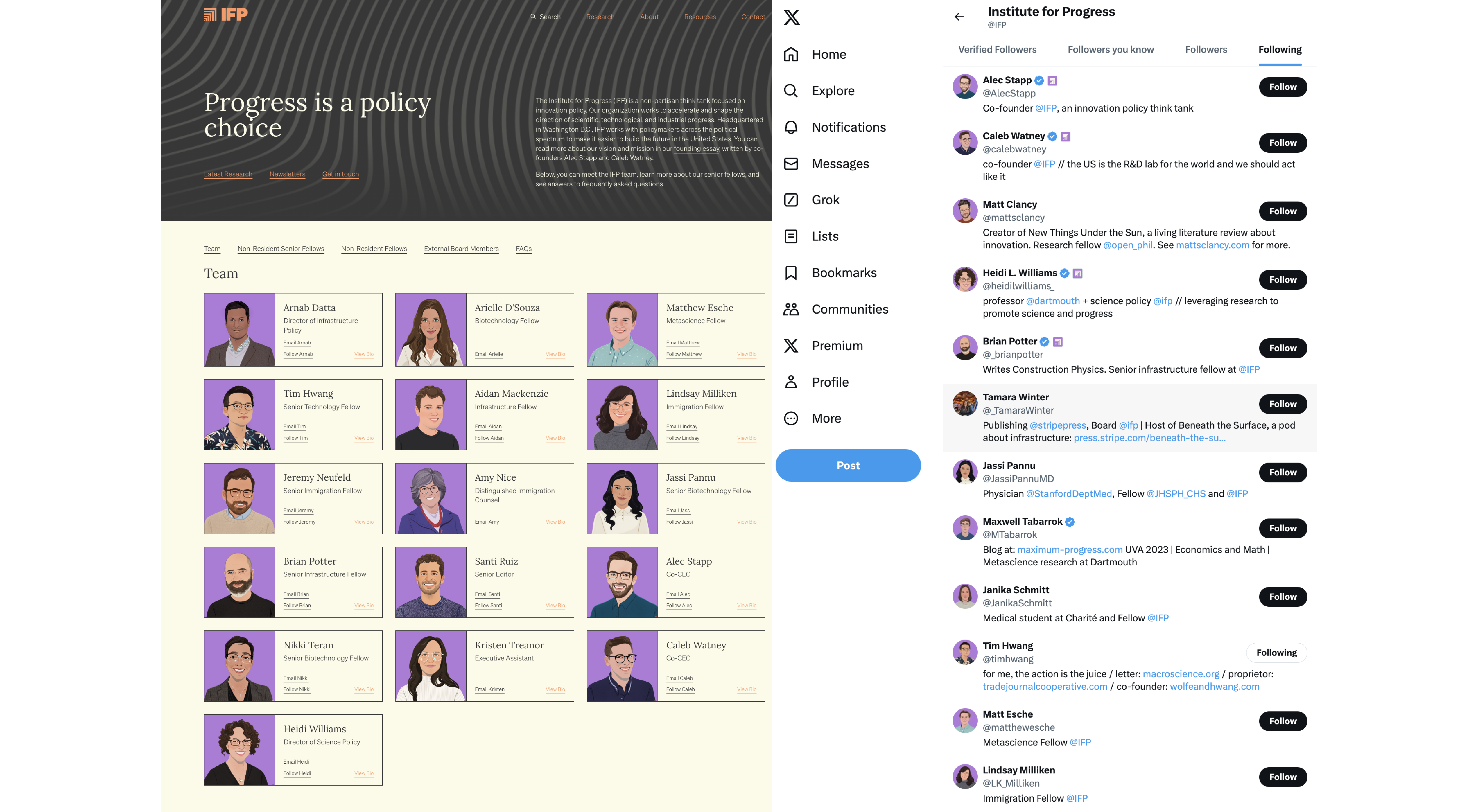

Whether it's a new visual style or writing tone, reformed communications practices are best guided by a proactive brand strategy. Small tweaks can be an easy way to get the ball rolling, but putting on bandaids often just leads aesthetic dissonance over time. The IFP stands out to me as a compelling example oh how a well-designed, cohesive brand can aid an organization's communications goals. What's particularly of note with IFP's brand is how it speaks towards a sense of 'headlessness,' (see earlier in this post). Take for example the cartoon illustrations IFP commissions for all its employees and fellows. These unique illustrations, which are used not only for headshots on the IFP website, but as social media avatars as well, are compatible with idea that modern brands exist in multiple digital contexts at once. Scrolling through X/twitter, individuals in IFP's orbit see the trademark purple-background cartoon avatar and passively get a sense for the organization's influence. This headless branding has a clear ripple effect back on IFP's advocacy work. Critically, it pulls this off in a way that involves no ads, no brainwashing, no email campaigns, nor any traditional form of marketing.

IFP's trademark purple avatars

What the IFP understands well is that a brand is more than a nice logo, it's packaging for a set of ideas. Brands are the glue that binds together components of what Nadia Nadia Asparouhova calls an 'idea machine' — the loose assemblage of entities that act together to evangelize a worldview. IFP is a think tank whereas OP is a grant maker, and so has it has more of a clear mandate than OP to dabble in the game of ideology. But this is not to say that OP is immune from it either. OP might not itself be an 'idea machine,' but it sits inside of one (EA).

An OP that does more storytelling, uses more images, would undoubtedly communicate better. But in order for OP to be great at communicating, it needs to pursue these activities as an extension of a compelling brand. At the moment, I would describe the OP brand as unremarkable. On the OP website, its mission is stated as "helping others as much as we can with the resources available to us." The OP logo could easily be confused with a tech startup. It's sans serif typeface is distinctly unoffensive.

I'm sure the intention for OP's brand was to not draw attention to itself, and to draw it towards its research and grantees. The outcome of such restraint though is worse than merely being forgettable. OP doesn't do unremarkable work. It's very consciously trying to change the world. When an unremarkable brand is layered over ambitious work, what's left is a feeling of distrust. Consumers in a hyper-savvy branding environment have developed remarkable detection for the playbook of inconspicuousness. In the wake of decades of politicians and corporations who've attempted to skirt controversy via concealment, there is no such thing as saying nothing.

What's worse is that OP is not a standalone grant maker. It's intrinsically embedded within a larger movement. Any amount of brand neutrality it lays claim to is immediately subsumed by the brand of this larger movement, which in the case of EA, happens to be divisive.

One of the main reasons I've hemmed and hawed about writing this piece for years is because I actually feel like publicly allying myself with EA (even in a critical capacity) reflects poorly on me. In a time where virtue signaling runs rampant, somehow the movement tasked simply with Doing the Most Good came to be viewed by some as an exclusive cult for ~~nerds~~ rationalists. If this is internally known already by EAs, I'm sorry for saying the quiet part out loud. If it's news, I'm sorry for breaking it to you.

It's difficult for me to speak towards EA's brand woes without coming across as unnecessarily harsh. For what it's worth, everything I say here is out of tough love. In hopes of not digging the dagger any deeper, I'll leave it at this: I've very intentionally spent my adult life trying to surround myself with friends and peers who care about the world and positive impact on it. Not a single person in my network calls themself an EA. Only a few even know what EA is. Not a single person knows about OP.

If my own anecdotal evidence doesn't resonate, consider evidence in the form of the backlash that surrounds EA any time it makes the news. Whether SBF or AI Acceleration, the reason why these controversies have ultimately reflected poorly back on EA is because there wasn't any strong preexisting public narrative (aka brand) standing in place to deflect unfair judgements. Once again, there is no such thing as saying nothing.

So what does it actually look like for OP to improve its brand? Throughout this post, I've gestured toward notions of human-centricity, empathy, legibility, engagement, and story-telling. I worry that EA loyalists might see me using these terms and think that I'm advocating for something that EA is fundamentally not. To be clear, being good at branding doesn't mean blindly chasing notions of popularity or coolness. Matter of fact, these positions are quite weak when taken on inauthentically (see: ex 1 and 2).

OP's great branding opportunity lies in leaning into what it already is, and doing so with a little tenderness and honesty. To do this it needs to take 'openness' more seriously. Sure, relative to many foundations OP is already quite open. But much could still be improved when it comes to the part of openness that implies legibility. As discussed above, openness only means so much if presented in a style and medium that is not accessible. Libraries are technically open and free to use, but librarians exist because parsing through an empty room filled with piles of books would not be an easy task for everyone.

I want to know the behind-the-scenes of OP's style of philanthropy. I want to know what the office looks like, what a hypothetical meeting between Emily Oehlsen and Cari Tuna sounds like. More than anything else, I want to hear stories from the frontlines of grantees' work. I want see the visual evidence of progress. For an organization that calls itself Open, none of these things are easily accessible at the moment, even if textual breadcrumbs are scattered across the OP blog.

If OP was to treat the practice of openness more expansively, this would reflect back positively on its brand. Instead of being suspected of 'open-washing,' or worse, being framed as just another shadowy philanthropic arm of a billionaire, OP could project a a culture of transparency and participation. This would have the effect of inviting in new fans and followers that wouldn't traditionally find their way to OP. It would also help push back against the narrative that philanthropy is anti-democratic. In turn, OP could become more resilient to controversy, for it's these same neglected out groups whose mischaracterizations directly feed public backlash.

Conclusion - towards an Affective Altruism

I want to end this piece offering up a vision for how, through improving its communications and brand, OP could catalyze an improved EA, one that is not just more open and humane, but more impactful.

Compared to other world-changing ideologies, EA's premise is relatively unimpeachable. Do the most good. As I've discussed in this piece though, these simple intentions do not reflect the complex cultural context that EA finds itself in. Despite its global, means-agnostic focus on reducing suffering, and despite its technical openness to outsiders, EA is a fairly isolated tribe. What's more is that it's a tribe that prides itself on rejecting some of the most universal human values, whether it be it appeals to storytelling or even just straightforward emotional intelligence.

It's not hard to imagine how things got this way. In the same act of distancing itself from the warm-blooded fallacies of altruism-past, EA over-indexed on rationalism and logic. It created a culture and brand of logos over pathos and attracted followers who were predisposed to these things, only further entrenching them.

As tightly bound as EA is to its unique brand of altruistic intellectualism, I don't see why there can't be room for a little sugar on top. Let the bedrock of EA remain exactly the same — finding ways to spend time and money that yield the greatest impact, even if they don't have a charismatic, present-tense face attached to them. Wherever these impact opportunities do lie, let them be communicated in a way that gives the wider public substance to attach to. If a face doesn't exist, illustrate it. Attempt to express suffering in both quantitative and non-quantitative terms. God forbid, partner with a celebrity. Use videos and pictures!

As a final source inspiration, I want to share my friend Henry Howard's personal giving project he called Workathon. The premise of Workathon will be recognizable to any EA. In 2021, Henry gave away half of his income to effective charities. Where the project stands out to me is in the simple videos and endearing title cards that he made to explain each round of giving, as well a slick data visualization that summarized the entire year. With just a modest appeal to humility, humanity, graphic communication, and humor, Henry made his philanthropic deeply memorable without any penalty to impact.

Now that it's been around for ~two decades, what is EA's legacy? Is it the incredible generosity and selflessness of adherents like Henry? Is it the hundreds, if not millions of lives that the movement has already saved, or the future lives that it stands to protect? Perhaps a well-meaning observer would recognize these things. But we live in an age of irrationality and absolution. Tragically, good intentions mean shit. For many, the legacy of EA is not its impact, but its reputation for ideological extremism. They point to the fixation over bug nets before the children the nets cover. They prod at the doomsday scenarios surrounding an AI accelerationist, or the nefarious actions of a single cryptocurrency fraudster.

It seems like philosophers and evolutionary psychologists have forever studied the question of if 'true' altruism exists, if we are capable of helping others, not because it positively reflects back on us, but because it's the right thing to do. EA has always appeared hellbent on implicitly proving that selfless altruism is in fact a thing. But what has this achieved?

Something I've attempted to argue in this piece is that, if done responsibly, appealing to imperfect forms of altruism can actually create more impact. EA is fundamentally concerned with advocation. It aims to create awareness and action around issues that not all of society cares about. If it was able to better communicate the importance of these issues to wider swaths of the population, even if it meant appealing to sentimentality, this could expand the net impact of the movement. I want EAs reading this to understand that affective altruism need not be incongruous with effective altruism.

The truth is that EA may be too big and too risk averse to change its culture in any meaningful way, especially from a single essay. OP on the other hand is much smaller and nimble, while still acting as a figurehead for the entire EA movement. I've targeted my appeals in this piece to OP because ultimately I think it could be a vessel for reform. Through modeling a progressively legible style of communications work, OP can advance its own goals while helping EA better confront the ways that the world is broken and imperfect. In a time where there is much suffering but also much confusion about what to do about it, OP and EA stand to create a culture of dignified agency. They can only do this though if they confront the vital fact that knowledge is nothing without communication and communication is nothing without translation.