Costco Capitalism

2019-12-16

It always strikes me when I run into a friend who is amused that I am a Costco member. For someone who grew up in a suburban area, even with the nearest Costco being a 45-minute drive from our house, shopping there was a no-brainer for my family. The reasons why Costco made sense for us are probably not dissimilar from the reasons of its ~100 million other members. Since its founding in 1983, the store has consistently delivered on providing value by selling almost any kind of product at competitive prices (among other things). In a 'late-stage-capitalist' landscape riddled with examples of, at worst, blatant greed, scams, and ripoffs, and at best, inadvertent marginalization from platforms, shopping at Costco is one of the few places that, according to its loyal customers, "feels like winning."

It's this near universal sentiment shared by its members that has made Costco a powerhouse (currently #2 in the world) in the retail sector. While some of my city dwelling friends in their twenties might find it amusing to shop at Costco, for millions around the world Costco is a mainstay. Even as the retail mindshare has been gobbled up by internet-savvy, D2C lifestyle e-commence brands, Costco has continued to thrive in the not so hidden background, and will continue to thrive for decades to come barring some radical departure from the very way capitalism works. And yes, that is with taking into account Amazon's dominance.

The point of writing this piece is not to talk about how specifically Costco operates — how it sells $4.99 rotisserie chickens, $1.50 hotdogs, or its strategy behind store layout. There are many other articles, generally of the MBA case study variety, that have done this already. (I do suggest you take a look at these though because they are actually quite interesting. Included are high profile lawsuits over golf balls, $420k diamond rings, and a poultry megafarm in Nebraska).

Instead, what I want to talk about here is the sum of all these components — how Costco can sell all of its products for low prices while making employees and customers happy. While other companies such as Costco competitors Amazon and Walmart also operate with versions of this low price, low margins strategy, Costco diverges because it arrives at low prices through psychologically favorable tactics for involved stakeholders. This is business speak for 'Costco can sell things for the lowest prices and step on the least amount of toes.'

Unpacking the reasons for this success reveals a crucial reframing about the resiliency of consumer psychology, even in an era where the negative impacts of consumerism are better known than ever. Having any kind of claim towards a more sustainable capitalism is just one of many methods a corporation can use to make consumers feel like they are winning. Unfortunatley this is a strategy that can be costly and finicky. And in a free market system where the path of least resistance reigns supreme, it often is far easier to win over customers with value from cheap prices than it is from morality.

Costco is a way to understand the (literal) 'formula' of consumer psychology and customer value, the variable blend of factors that a corporation can use to draw favoritism, as well as the inherent biases that are contained within it. In this piece I will offer an explanation for how, amongst all-time high levels of backlash against corporate hegemonies, amongst a threats like climate change clearly driven by our consumer habits, Costco has been able to cement itself simultaneously as an inculpable crowd favorite and mothership of bottomless consumerism. I will ponder whether or not consumer happiness or value is the best proxy for individual (and environmental) well being, whether or not you can truly have your free sample and eat it too.

Costco 101 - Building a structurally 'fair' company

Based on reputation for consistency and great labor practices, some may think that Costco is deeply principled company. Unfortunately, paying employees livable wages in 2019 is still something that is unusual for a corporation of Costco's stature. Yet Costco's minimum wage is $15 an hour and its average wage is ~18/hr. It may be the case that Costco is principled, but not necessarily in the philosophical sense of the word. "We are not the Little Sisters of the Poor," said ex CEO James Sinegal. "This is not altruistic. This is good business."

Costco's principals can be thought of as simple truisms, guide posts for smart business acumen. Above all other things, Costco aims to maximize consumer value. It does this mainly by selling their goods for competitive prices, even though a decent argument can be made that Costco has other business objectives contained in its mission like treating employees well. Deeper inspection of the way Costco works shows that its fair wages are more of a business strategy (that actually keep prices low) than they are altruism. As illustrated Costco 101 below, Costco's warehouse model means that they have low overhead costs and therefore need fewer employees to carry out their operations. Compared to Walmart who earns $235,450 of sales per employe, Costco earns more than twice the amount at $744,893. This means that they can increase individual employee wages, which in turn increases talent and retention levels, which in turn increases customer happiness, which in turn increases membership sales ... you get the idea.

Costco 101

To shop at Costco you have to be a member, which entails paying an annual membership fee.

- Buying a membership constitutes a sunk cost, and so members feel inclined to shop there enough so that they 'pay off' their dues.

- Shopping at Costco exposes you to the way Costco works, its unique quirks, which generally makes you want to shop at Costco more. Also being a 'member' helps shoppers feel a sense of belonging and exclusivity.

- In addition to membership sunk costs, nostalgic perks like subsidized rotisserie chickens and hotdogs, and free samples help retain members.

Costco sells one version of pretty much every standard consumer good

- ~4,000 total SKUs (items) compared to the ~30,000 found at supermarkets

- They are picked for a) high quality / price ratio b) appeal to mainstream tastes

- For lower unit price products (rice, milk, socks, etc.) they are sold in bulk quantity

Choosing to sell only 1 version in of a thing in bulk means Costco can

- sell more of the product per transaction

- negotiate better prices from manufacturers and suppliers

- sell at lower margins

- move through inventory quickly, and therefore allow the selling of fresh food/produce

- lower number of trips to store through increased single trip purchases

Costco sells its goods in unfinished warehouse on prepackaged pallets, which means

- lower overhead / maintenance costs

- fewer employees per product volume/square footage

- can afford to spend more money on employee's wages

- happier employees and better customer service

- further savings passed on to customers

All of these things together

- Costco is a cheaper way to shop for almost everything

- Costco doesn't need to market itself

- Costco is a happier retail environment

- Costco creates happy, repeat customers

Which in turn means:

- Costco gets more business and opens up more stores

- Costco can negotiate lower prices with higher purchasing power and economies of scale

- Costco attracts more members

Much has been said of the Amazon's "flywheel" — it's strategy of having disparate parts of its operations connect through positively reinforcing feedback loops. A simple example:

- Be an Amazon Prime member so you watch a TV show that's only on Prime Video

- Buy an Amazon Fire TV stick so you can watch this show on your TV

- Use the device more and send this usage data to Amazon

- Amazon knows more about what makes better TV

- Amazon produces better original content

- Amazon makes Prime Memberships more compelling

- Repeat

We see with its approach to employee compensation that Costco actually operates within a similar logic, but with a certain elegant simplicity and not as many moving parts. If Amazon is a flywheel, Costco is a pulley where a few highly transparent cost saving measures all lead back to the goal of passing savings onto the customer.

Unlike the hydra that is Amazon, Costco's simplicity means transparency. Each stakeholder in its flywheel — namely employees and customers — are met with straightforward terms. Walk through a Costco warehouse and you literally shop off of shipping pallets, seeing the evidence of your cost savings real time. The efficiency enabled by the constraints of selling in bulk and in a warehouse means that there are no breakneck distribution centers or workers rights infringements, no data capture scandals, no suspicions of geopolitical dominance. Costco does what every consumer in a 'neoliberal' economy wishes corporations did more of — find success by simply playing along with the rules fairly, not bending them to their will.

Listen to this interview of Costco's current CEO, Craig Jelinek to get a first hand glimpse of how baked in fairness is in the company culture.

All in all, the point to drive home here is that Costco has set up a business that is structurally possible to operate fairly. For many traditional corporations, Walmart being a good example, you could make the argument that the exact opposite is true. In the long run there is no union-busting or PR campaigns that can get around the fact that it is structurally impossible for Walmart to pay the same wages as Costco given their business model.

The Cult Of Costco - How fairness creates psychological favorability

What are the results of Costco's fairness? Quantitatively speaking, Costco is a very healthy company. It has grown steadily since its inception, through boom and bust, and in just the past year has doubled its stock price. Wall St. loves to rank on Costco for not maximizing short term shareholder value through short term cost cutting measures (i.e. cutting wages) but you could argue that for long term holders, Costco's stock is aided by these non extractive values. One illustration of this is that despite the ongoing 'Death of Retail', Costco has never closed a retail location over bad performance. The same can't be said of many other retail rivals, including Costco's closest wholesale counterpart, the Walmart-owned Sam's Club.

More interesting than financials though is Costco's qualitative lure. More than any other retail store, maybe even more than any company of its size, Costco is revered by its customers. There are third party subreddits, twitter accounts, instagram pages, blogs, and fan forums all devoted to the store. When Costco members talk about their experience they sound more like hobbyists than consumers.

This phenomenon would be unusual for a publicly traded corporation on its own, but what makes it more remarkable is the fact that much of this attention is not the product of some guerrilla marketing strategy. Matter of fact, Costco doesn't do much marketing at all. Its twitter account is nonexistent and it has an instagram devoid of influencers, lifestyle shots, or really people at all. It's just pictures of products. Costco's only marketing artifact is interestingly a monthly editorial magazine called 'Costco Connection' that simply aims to recirculate the zeitgeist of the store and its shoppers. The overall lack of effort it puts into traditional marketing channels is just another illustration that Costco's admiration is mainly organic.

Even if unintentional, Costco teaches us something important about the state of marketing in a post-authenticity corporate landscape — what it means to be favorable during a time where corporations are across the board unfavorable and no amount of retouching can augment this perception.

Be Structurally Unimpeachable - aka Don't Can't Be Evil

The first lesson and starting point is echoed above with talk of Costco and the differences between its business model and other retailers: the flip side of operating a structurally fair business model is that it can provide the armor of structural unimpeachability.

Structural unimpeachability is conveyed in a more palatable way through a tagline/concept recently developed by the blockchain app platform, Blockstack: "Can't Be Evil." Can't Be Evil is of course a reference to an earlier Google line, "Don't Be Evil," which was their unofficial motto and even in the company code of conduct before being recently removed. While Google would never say this, the obvious reason for them removing the slogan was that as a company it is increasingly impossible for them to keep this promise. The very way that Google works requires at the very least a little bit of evil — that is at least if you associate surveillance with evil. Way before they removed this line from their documentation in 2018, the public already knew this.

Blockstack, and other similar web3 entities came to rise broadly as a counter to tech corporations that were caught being evil. Their claim was trustlessness, and that through the the public ledger and hardcoded, verifiable software logic, one could shift from merely convincing trustworthiness to proving it. Thus, these new organizations "Can't Be Evil."

Now of course, the endless scams and get rich quick schemes across the blockchain space seem to prove that technical trustlessness is a very hard thing to pull off, but what's important for the conversation here is underlying sentiment that is contained within it. Whether it's in technology or politics — what people crave now more than ever is trust. Simultaneously, it's easier than ever for us to realize the cheapness of words and promises. Given the impossibility of trust, people turn to trustlessness.

For Costco and many other companies that operate in the messy logic of physical commerce, achieving trustlessness is also very hard, if not technically impossible. In light of this, trust can still be generated, but not solely from marketing talk. This leaves the closest thing to trustlessness as creating a business model that structurally can't be evil (or at least appears this way). This is exactly what Costco does with policies like employee compensation and what leads to their positive reputation.

Manipluating the Formula for Consumer Value

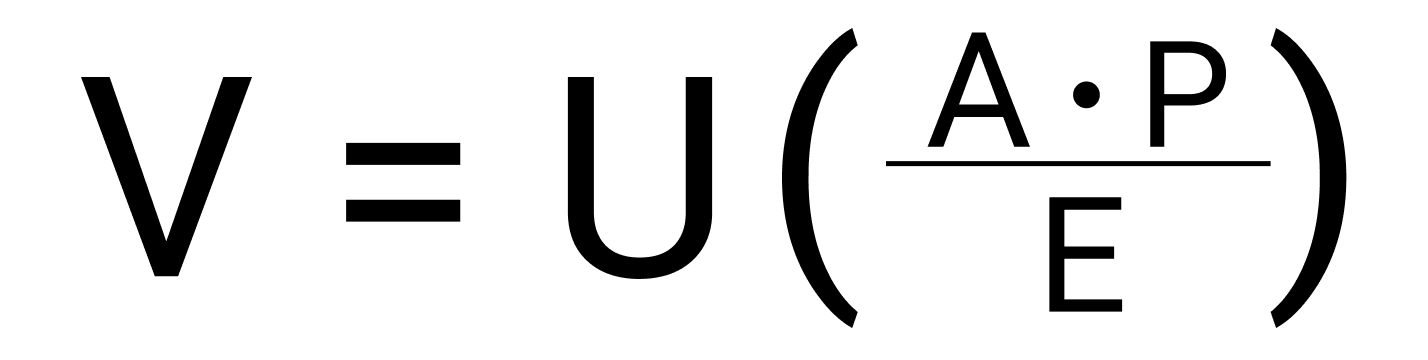

Costco would never have grown to be so favorable if it simply never got caught being evil. To actually go and create value for its customers the store has has to go beyond this. Consumer value is a subjective expression at best, but consider this formula:

where v = value

U = economic utility

A = attractiveness (which is product of psychological influence and positive externalities)

P = price discount ratio

E = (negative) externalities (which is a product of experienced externalities / perceived externalities)

Here is a more thorough explanation for this formula:

Value is before anything else a product of a economic utility in the microeconomic sense of the word. Upon interacting with Costco, consumers ask themselves, either consciously or unconsciously how much utility that interaction caused them. In addition to this though, there are certain variables that augment this utility. One such variable that augments utility is attractiveness - or put simply, how adored Costco is both as a brand and experience. Here, Costco has some crucial elements weighing in its favor such as the nostalgia that its food court brings out for its customers, the generous free samples, or its reputation for fair pay.

Additionally the price discount ratio, or how discounted Costco goods are relative to similar goods at other stores, is something that heavily increases the value of Costco, maybe even more than any other variable.

On the other hand, customers also perceive other variables as decreasing overall value. These can be summed up as an exchange's negative externalities, which consist of any effects that constitute environmental or social harm. These effects are weighted more heavily based on whether they are directly experienced compared to if they are merely perceived/known.

The point of citing this formula is not to quantitatively define value, nor is it to even suggest estimates for what the average consumer value gained from a Costco interaction is. I merely want to point out a couple of things: 1) everyone applies different weightings to different variables in the value formula 2) the weightings of these different variables can simultaneously be in direct support or opposition of one another.

The takeaway is that value can be decreased by negative externalities, but that it also can be positively effected by a product being affordable. When push comes to shove making a product sufficiently cheap can outweigh any negative externalities that come with it, especially if these externalities are just weakly observed instead of intensely felt.

Some Examples:

- Apple products are dramatically more expensive and are associated (at least more so in the past) with the negative externalities of supply chain and labor abuses. But they are highly attractive and thus generate a lot of value for their consumers.

- Riding a bus is dramatically cheaper than ride sharing or operating a personal vehicle, has positive externalities associated with it, but for some is seen as significantly inconvenient and unatractive compared to these other options. Even considering the well documented negative externalities of Uber, its raw utility creates more value for many than riding the bus.

Bringing this back to Costco and its ability to create value for its customers, we can see that affordable prices are the significant driver of customer value. And even though shopping at Costco comes with negative externalities (mainly those associated with overconsumption, waste, and sustainability), the perception of these externalities is quite low from the point of view of the average Costco consumer. A mainstream environmentalist knows well that the consumption of inexpensive beef is problematic, even if it's grass-fed organic. But the average Costco shopper is not a mainstream environmentalist. Furthermore, there is the known positivity externality of supporting Costco's high paying retail jobs that masks these negative externalities, if they are perceived at all.

Sustainable Capitalism? - What Costco shows us about the blurry relationship between ethical and fair

Costco shows that neither disruption nor innovation itself is the thing that draws favoritism. Rather, simply providing your customers the feeling that they aren't getting ripped off, and doing so in a way that matches mainstream views of acceptable externalities, is all that is required for success. If this sounds reductive, it's because it is. The key to Costco's success is just how straightforward the alignment of stakeholders within its business model are.

That being said, there are externalities associated with Costco's business model, even if they aren't viewed by the mainstream as such. The main thing here is a retail model that promotes rampant consumption, and the fallout from this which includes broad waste and sustainability concerns. Interestingly, because of Costco's large purchasing power, dominance over its supply chains, and upper-middle class income of its shoppers, it generally has more progressive product standards than other retail brands in comparable price tiers.

A rather long footnote from Costco's web page on animal welfare

A rather long footnote from Costco's web page on animal welfare

For instance - take Costco's stance on animal welfare practices. It's clear from even this fairly corporate-speak page that Costco understands the importance of animal welfare, and takes its responsibility in the manner seriously. It has a "Animal Welfare Task Force" and follows the 'gold standard' of animal welfare practices in the form of the Five Freedoms of Animal Well Being.

But would you be surprised to hear that Walmart — one of the most (at least historically) notorious committers of animal right abuses — also supports this pledge? There's no doubt that these positions aren't meaningless, yet determining what such statements mean for the day the day operations of Walmart and Costco's suppliers, what the true impact of these positions amounts to, is currently only as effective as the investigations of a set of fringe environmental watchdog groups. This is the unfortunate reality of public diligence that corporations like Costco, Walmart, and Amazon take advantage of. While it's true that ethical practices are more important than ever, there still is a massive buffer between the actual operations and impact of these entities and the investigative legibility of the fourth estate. Even then there is yet another gap in terms of the ability of the public to actually interpret and act upon the findings of this fourth estate.

Yet this communications buffer is growing weaker over time. We are living in a time where the operating practices of corporations are increasingly susceptible to the critical gaze of the public. The public and the 4th estate are less separate entities that an amorphous blob. This is for many reasons such as increased public skepticism and widely accessible publishing platforms. These factors mean that dubious practices that previously existed behind closed doors are now just one post away from becoming a public and cancelable offense. The facade of PR or marketing is increasingly ineffective against the creep of public scrutiny. We're seeing that increasingly, projecting a positive image is not just a nice-to-have.

In light of this shift we have seen many businesses rebrand themselves as derivations of woke, sustainable, or ethical. But for many of these entities where positive impact was used as a sleight of hand trick to leverage virtue in place of value, nothing can distract the public from eventually asking a basic question around whether or not a given entity is actually being fair to them, their environment, or society.

This is not the point we are at yet though. To be clear, we have by no means established any kind of accurate litmus test for what constitutes fundamentally good or bad companies, and externality perception is different for each consumer, as illustrated by the Value Formula from earlier. Matter of fact, online virality and cancel culture suggests that this distinction can be mercurial and heavily influenced by social forces. But this is beside the point. A consumer's tastes are a consumer's taste. For all the power a corporation has, it is ultimately only as powerful as its ability to win over as many of these tastes as possible. After all, hasn't marketing always been hinged upon playing with the fraught nature of favorability?

Connecting this back to Costco's business model, it's goal is to increase V (value) in as many customer's value formulas as possible. This is the, once again, reductive starting point for understanding their appeals to ethics. Costco is not a principally moral company. It's moral only to the extent that it can do this while creating the same or higher amounts of value for its customers. It doesn't set but follows the standards of decency of its customers. A simple illustration of this that explains not just Costco's but Walmart's somewhat progressive stance on animal welfare is that for the majority of Americans, 'clean' meat (meat which is free from unnecessary antibiotics and hormones) is recently the kind which is in the highest demand. Selling to this demand is good business before it's altruism.

Costco's responsive stance on issues like animal welfare, how they are willing to bend to pressure if it means selling more product, is the key to its success moving forward, and also an important foil to the very idea Of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) - that corporations should be in the driving seat when it comes to setting standards for ethical operation. Costco shows why so many of these initiatives set off our b.s. detectors — they are conveniently profitable (or at the very least a tax write off) before anything else. Any additional positive impact that follows is often just an added bonus.

CSR Shortcomings in the Long Run

Earlier we talked about Costco’s overwhelming fairness (summed up as cheap prices and high wages), and how this creates an environment of structural unimpeachability (aka “Can’t Be Evil”).

The funny thing about a statement like 'Can't be Evil' is that it combines a boolean and subjective expression. How a given entity defines 'evil' is very much open to interpretation. Some might see Google's approach to surveillance as totally reasonable while others associate it with the worst kind of toxicity. In the context of Costco, evil — or put more simply, ethics — is approached with the same subjectivity.

In corporate governance, being evil is not actually the crime; it's being judged for being evil, or worse being cancelled entirely that is actually the outcome that effects the bottom line. Traditionally this has meant that as long as you had a good enough PR and legal budget, you could do some fairly demonic things and still redirect any negative attention away. But in the past two decades there has been an increase in legibility around the externalities of business, alongside a rise in the publics' standards of decency. This combined with a plethora of viral publishing mediums means that all it takes is a single tweet to change the entire fortunes of a company.

The key to dealing with this sensitivity is knowing precisely what constitutes evil and for whom. If you think back to Costco's business model, it sells a small number of products in incredibly large quantities. In order to sell products in bulk, you need to sell precisely to mainstream consumer tastes, which might mean slightly different things depending on which broad demographic you cater to. The fringes simply do not have enough purchasing power. To do this Costco not only has to create products that fit perfectly into its 'consumer overton window' but they also need to hold up to ethical standards of this population.

As clean meat, organic produce, designer supplements and protein powders, and Airpods, all move from luxuries of the rich to commodities of the middle class, Costco is the canary in the coal mine for this transition. Embodied in the increased demand for these products is the increased demand for the ethical values they represent. While Airpods might not have much embodied meaning, fair trade bananas, paleo bars, and acaí smoothies do.

Interestingly, for the purpose of grasping Costco's ethical boundaries, you have to look away from their embrace of wellness trends or organic foods. Instead it's the Costco best sellers that have been in the stores for literally decades — like the $4.99 Rotisserie Chicken or $1.50 Hotdog — that actually speak the best towards the store's Overton window. That you can simultaneously crave cold pressed juice, but not bat an eye at the inherent questions of sustainability that surround a $1.50 1/4 pound all beef hot dog seems to embody the Costco ethical stance well: Sustainability or Ethics are not things rooted in facts but perceptions.

Costco shows the futility of this kind of neoliberal logic — that ethical concerns can be clumsily and painlessly shopped around. Once again it's in this almost apolitical stance that Costco reveals a lot about its ethics, and its subsequent perception from the public gaze. Costco is not an ethical maverick or trend setter. It is a trend follower, both in culture and product. It's through swiftly following the lead of its mainstream customers that Costco is able to circumvent the PR crises that surrounds much the corporate landscape right now. Costco can never be seen as Evil because that would mean the bulk of its customers view themselves as Evil.

This reveals a problematic Catch 22 that sits at the center of this piece. Corporations only act as ethical as their subset of consumers, and consumers only are pressured to only act as ethical as their value-maximizing formulas allow them to be. This means that making a premature leap towards offering more progressive yet more expensive products or services comes with risk. Risk averse corporations, especially large ones like Costco, have to be completely sure that a market has come maturity before they offer up a product that represents a premium shift in its consumers' ethical frameworks.

So if the golden child of consumerism, a lovable and ‘fair’ company like Costco is only as ethical as the bulk of its shoppers, where does that leave us? In the short term Costco might technically represent a pragmatic balance of entertaining a more sustainable version of consumerism than Walmart or Amazon, but this is like calling a large oil producer the most climate-friendly. At a certain point there is an inherent incentive problem that needs to be recognized.

Looking forward, the optimist might say that the public’s increasing legibility towards impact and increased ethical concerns means that Costco will be pushed towards practices that are less extractive, and that the collective impact of these choices will be non insignificant. But will the pace of this shift be timely enough? The pessimist might note that if there’s anything that we know about our resource consumption, it’s that we are far better at choosing what is cheap and easy in the short term than we are adequately pricing sustainability into the future. The ‘E’ (externalities) in our value formula will be weighted more over time, but will it ever be weighted appropriately? Our collective inaction towards climate change should be evidence enough that consumers alone cannot be held responsible to correctly internalize externalities.

Some have addressed this future discounting problem through the lens of providing different choices to consumers. If Costco isn't progressive enough, what about Whole Foods? If Whole Foods doesn't do the trick, what about the local farmers market? The problem with these choices is that every step up in ethical consumption comes with a slashing of consumer population size and the economies of scale that come with more mainstream options. Your backyard organic produce is just this — a solution for an increasingly small radius.

Instead, what is far more impactful is to figure out not how to increase the amount of consumers that fall into these increasingly expensive, discrete consumer tranches, but to convert preexisting tranches into more ethical operation frameworks.

Another way to get at this idea is that instead of adding/removing variables in formula for consumer value as a way to create more equitable outcomes, it's easier to actively influence the weighting of the formula's preexisting variables. There is much less resistance working within a system as opposed to reinventing it. If you are interested in how a set of companies and consumers can be the most impactful possible in as pragmatic a way as possible, your best bet isn't necessarily to disrupt capitalism with aspirations of circular economies, back-to-landing, social entrepreneurship, or any of its other silver bullets. New solutions are important, but only if such rhetoric doesn't step over the impact of taking previously existing institutions and retrofitting them towards better outcomes.

So what are the tools at our disposal currently to influence a mainstream consumer's weighting of 'E' to be more accurate? Things like certifications, investigative journalism, and sensational marketing are the most common ways we get consumers to augment the weighting of the impacts of their shopping. Even it constitutes fighting fire with fire and often devolves into virtue signaling, there will continue to be a role for these strategies.

How these strategies fall short though is that they achieve their increase in environmental or social legibility through a medium or third party. In the long term we will see those communicating impact attempt to dissolve this intermediary through increasingly immersive mediums that lead to heightened awareness. Whether through VR which has been proven to lead to increases in short term, 'affective' empathy, or the wielding of utilitarian frameworks like effective altruism that promote a more honest reflection of underlying impact, consumers will be drawn towards channels that bring them closer to truth.

This is a shift that can be taken advantage of by more than documentarians and nonprofits. I believe that retailers like Costco can play this game too. Instead of reacting to the slow evolving standards of decency of its shoppers, there's nothing that's stopping a company from playing a more proactive market making role as long as they accompany this push with convincing evidence for consumers why a new offering is valuable for them.

With all that being said, is this scenario likely for Costco? Probably not. Have you ever tasted a $5 rotisserie chicken?

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Toby Shorin for editing and feedback.

Additional thanks to Ross Zurowski, Rachel Victor, Callil Capuozzo, and Erin Frey for feedback.